My library has no walls, no soaring Bodleian dome, no ugly concrete exterior of a public facility, not even the bouncing, chugging metal carcass of the mobile library that visited my village each week. My library has only an interior, a vast space in which are stored all my thoughts. Here is everything that I have ever read, heard, experienced … In recent years this space has become less calm and ordered, less reliable, as I have moved from the clarity of youth through the ‘porridge brain’ of motherhood to the brain fog of middle-aged fibromyalgia. It has become a place in which I find frustration almost as often as understanding.

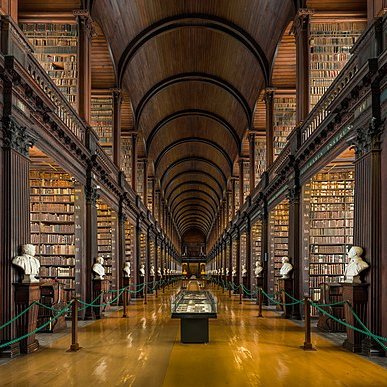

When I was a child, one of my images of heaven was a library, a vast and beautiful space in which the walls were lined with tier upon tier of books, sheltered under a glorious, gold-touched, vaulted ceiling. In this library were the answers to all the questions I had ever asked, everything in clear view, the books beautifully accessible within their perfectly ordered setting. In my heaven I could look forward to an eternity in which to explore them.

As an adult, with more than half a century of study and experiences behind me, my library is accessible in the here-and-now and not only in the hereafter. It is still a beautiful space, but that glorious chamber of answers is now only one room of many. It has become a dimmer, more complex place that shifts and changes with me like the Unseen University library of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld. Its rows recede into the distant gloom, tower over my head, and are crammed with volumes of all shapes, sizes and conditions. It is staffed not by Pratchett’s orang utang but by my own personal librarians.

At its heart sits my recalcitrant chief librarian behind an immense mahogany desk that in its very essence commands, ‘Do not disturb!’ While I sit at a laminated IKEA desk on a squeaky swivel chair, she lounges in the squishy leather armchair of my imagined childhood library, of my real university common-room. A glass lamp shade illuminates her book. She is as reluctant to answer my calls now as I ever was when lost in the world of Narnia or the Secret Garden.

I come in search of a name. I know it is filed away somewhere in the rows of polished-wood index card drawers behind her, but the labels have all been removed. It seems as if someone has thrown all the cards in the air and stuffed them back in again higgledy-piggledy. Her withdrawal leaves me stranded uncomfortably, mid conversation.

‘What’s the name of the character in that film? You know, the one who slides Angela Lansbury around on the library ladders while he sings to her? I think it begins with a P.’

My librarian has no pity and turns a page, but behind her a timid assistant begins a silent rummage through the wreckage of the index system. I know that she will find it, hours later when the conversation is long-finished, and I am actually looking for something else. Her appearance will be both frustrating and a reassurance that it is all still in there somewhere. I have not lost anything. I just need to do some serious spring-cleaning and to retrain and motivate my staff.

The chief librarian has no name. I suspect that this is withheld on purpose to limit my power over her. (‘You never ask anybody his name. You never tell your own.’ writes Ursula Le Guin in her Earthsea trilogy.) At times my librarian can be immensely helpful. If she is given plenty of warning and we are working together on a project she can work miracles, dredging up items that are perfect for my purposes but which I didn’t even know to look for. She knows with perfect clarity the meandering aisles of my mind and the miscellaneous box files that lurk on the top shelves. Everything is connected; one shelf leads to several more and she just needs a starting point for our journeys of discovery. We are old friends and adversaries. During school she was clad in jeans and doc martens, sporting the blue hair that I never dared. She lounged, feet up on that mahogany desk, reading historical fiction while I begged her to file the enormous piles of rote learning I was expected to memorise. Thank goodness for her reading, which contributed far more to my recall of the Tudor courts than my A level classes ever did. Once we made it to university she danced down the aisles of my mind, building new ones, adding shelves and making maps that connected every point to every other point. She had no need of the index card drawers, carrying everything in her back pocket instead.

Those back pockets began to bulge through years of nursing. Matrons, sisters, consultants, families, colleagues and social workers all insisted that I should have every patient and client’s name, and a complete command of their condition, history, friends and family, on the tip of my tongue whenever needed. Woe betide the nurse who hid behind, ‘I’m just back from holiday …’ As a mother, the demands escalated; the index cards multiplied like cells in a petri-dish as I tried to hold the entire family diary and the location of every possession within instant recall. I realise now why my index card drawers are a mess. My poor chief librarian must have emptied her pockets when their weight began to drag her down. They were never neatly filed, just stuffed out of sight in a panic at the immensity of the task.

Emilius Brown in Bed Knobs and Broomsticks. He was singing Eglantine.

Thank you Emily, that is most helpful (not). What I need now is the name of the botanist who sailed to Australia with a cat, but never mind.

I look at Emily (now why is the assistant librarian happy to share her name?) and wonder why I never noticed her before. I have always pictured my librarian as the person behind the desk who I addressed my queries to, missing the shadow flitting behind her, retrieving information without instruction. Emily is launched on her quiet quests by the non-verbal and the unconscious: a sound, a smell, a taste. She can bring me the unexpected joyful memories of relaxing with friends prompted only by a whiff from a quickly snatched coffee. She can bring back my father in a lungful of engine oil or cigarette smoke.

She can also flatten me in terror at the chime of a doorbell or the ping of a Facebook notification. Emily knows me far better than the chief librarian, better than I know myself. She is the shadowy queen of the cellars of my library where the chief librarian and I never venture. Unlike the Hogwarts library, my restricted areas have no Madam Pince patrolling the entrance. There is no turnstile, no security guard, no stairs down, indeed no clear entrance at all. These are places that I do not want to explore and yet they are a constant presence, sucking in my energy and threatening my peace of mind. I can find myself cowering under their threatening shelves without warning, not understanding the route that brought me here or how to get out.

I once read that grief is like a huge hole that opens under your feet and swallows you up. It takes time to climb out of the hole and continue with your life. The hole never goes away, you can only learn to see and avoid it, to build up the courage to stand on the edge and remember, plant trees and shrubs to soften the edges and mask the horrors. There will always be unexpected paths that plunge you back in again, but each time the way out will become more familiar. For lack of courage or a guide to help me learn, I have blocked off some of these holes, these cellars in my library, and so the fall into each one, when it does happen, remains frightening. The energy needed to keep these areas blocked explains their sucking, draining quality. I cannot just build a wall and dance onwards.

Emily has emerged from the shadows behind her chief to be my guide. She shows me how to notice those odd experiences: a tightness in the throat, a bizarre reaction to a smell, an odd turn of phrase in my critical internal monologue that doesn’t sound like me. We follow these physical experiences and anomalies like Ariadne’s thread into the maze. They lead me safely to the dark spaces where she shows me that there is nothing in this library that can hurt me; it is all in the past. Once there I can shine a light, explore the past from the safety of the present and see the exits. It is slow work but as I let the light into each dark room and sweep away the cobwebs my chief librarian follows behind, mapping our progress, filing and cross-referencing their contents safely for future reference. As we go, my energy builds and the realisation dawns, I can build a huge and joyful bonfire of those ridiculous index-cards and give my chief librarian the highest of high-tech smart phones instead. I do not need to be trapped in this brain-fog forever. I am middle aged not in my dotage and I have a whole life ahead in which to perfect and enjoy my library in all its light and gloom.

I wrote this after spending time reading around the issue of trauma and the way in which it is stored and embodied in ways that can continue to cause physical symptoms years later.

For anyone interested in knowing more try:

When the Body Says No: The cost of hidden stress (Gabor Maté)