Several Years ago, as part of trying to find my way back into work after a long period of being a full-time parent and carer, I set up a micro-bakery. I baked bread in my kitchen for friends and neighbours and taught myself how to make sourdoughs as part of this. I did this through reading the books at the bottom of this post, particularly Andrew Whitley’s Bread Matters, and watching YouTube videos. I am not a formally trained baker, just someone who loves learning how to make good food from scratch.

This post will not enable you to produce perfect sourdoughs instantly; my first attempt was more like a discus than a loaf. Like the bread itself, learning to make sourdoughs takes time. The challenge is to watch and understand how the living culture responds under different conditions and what it is supposed to look, feel and smell like at different stages. The learning is a lot of fun though and even the less successful loaves will taste good.

What is a sourdough?

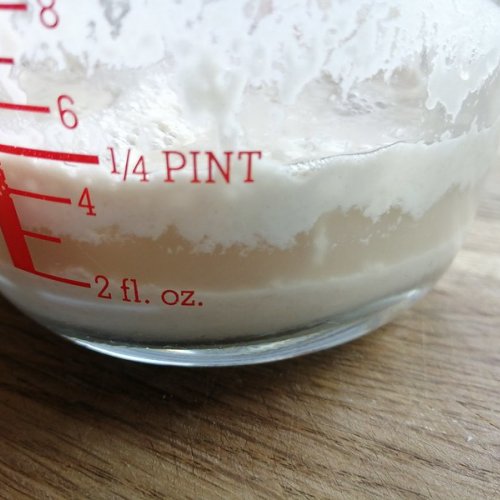

Sourdough bread is leavened with the wild yeasts that are in your flour and the air of your home, rather than from commercially produced sources. Read on to find out how to capture and grow these yeasts into a starter that is strong enough to raise a loaf. All you need for this is flour and water.

You could begin with a commercial packet of sourdough starter, but these are expensive and after a couple of weeks the expensive culture will have been colonized and taken over by the yeasts in your own flour and home. Embrace this! Home-made starter is cheaper and means that your loaf will be unique to your home and every bit as good. You really don’t need fruit juice, raisins or anything else people advise. People have overcomplicated an incredibly simple process.

N.B. If you buy sourdough and the ingredients list yeast, it isn’t a sourdough and you’ve been conned! Most commercial ‘sourdoughs’ have a little culture to add an acidic flavour, but are still raised rapidly with large amounts of industrial yeast.

Wild yeasts take longer to raise your bread, but produce better flavour and a slight sour tang. This comes from the lactic acid, which is a by-product of their growth. Bread that has taken hours to rise is more nutritious and easier on the stomach, as the culture has had time to begin breaking down the starch and proteins in the flour making them more digestible. Slow bread like this will also have a browner crust because of the starch that has been broken down into sugars. These then caramelise as it bakes.